RADICAL FOLK

A conversation with Ani Difranco and Utah Phillips, kindred spirits and

collaborators on a daring new album

By Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers

"People my age find folk music very uncool--it's just terribly,

terribly uncool," says Ani DiFranco. With her cropped, green hair, boy's

hockey jersey, collarbone tattoo, and spiked leather jacket with a sticker

on the back that says "Mean People Suck," DiFranco hardly looks like most

people's idea of a folkie--and her edgy, often frenetic music doesn't

sound much like most people's idea of folk, either. So what is she doing

here in Toronto at the Folk Alliance conference, an annual gathering of

the faithful presided over by such archetypal folksingers as Pete Seeger?

DiFranco is here because she has her own definition of the f word. "Folk

music is not an acoustic guitar--that's not where the heart of it is," she

says. "I use the word 'folk' in reference to punk music and rap music.

It's an attitude, it's an awareness of one's heritage, and it's a

community. It's subcorporate music that gives voice to different

communities and their struggle against authority."

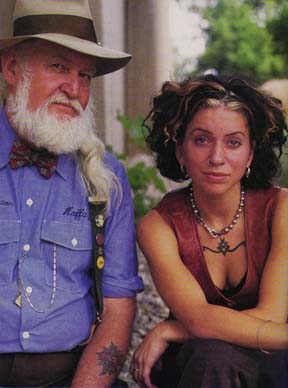

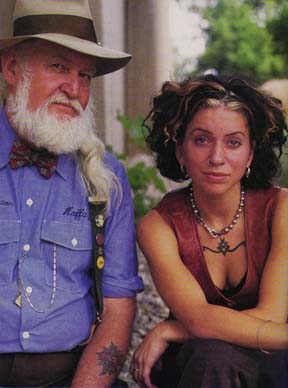

The fact that DiFranco defines folk by its spirit and intent

rather than its sound and dress code goes a long way toward explaining

her connection with Utah Phillips, the venerable singer and storyteller

who sits next to her in this hotel ballroom. From his fedora and

snow-white beard to his repertoire of labor songs and populist anthems,

Phillips is as unambiguously a folksinger as he could be--and as

stylistically distant from DiFranco as he could be. But appearances are

deceiving. Just a few hours ago, DiFranco helped present Phillips with

Folk Alliance's Lifetime Achievement Award, citing his gift for entwining

humor, entertainment, and politics as an inspiration for her own music.

This is only one of the many traits and passions they share; their

connection is so strong, in fact, that he's the first outside artist

DiFranco has brought onto the roster of her own Righteous Babe Records

label.

DiFranco's and Phillips' 1996 album for Righteous Babe, 'The Past

Didn't Go Anywhere,' is much more than a unique collaboration between a

folk elder and a rising young star; it's a bold and ambitious musical

statement, brilliantly executed. DiFranco sifted through 100 hours of

Phillips' live tapes and picked a handful of her favorite between-song

raps--the ones that, she says, "made me fall off my chair laughing or

just go off in the corner and cry and mull things over a while." She then

took those stories--chronicling Phillips' desertion from the army during

the Korean War, the mentors who taught him about politics and life, and

various philosophical observations from his years on the road and

rail--and holed up in an Austin studio to layer music tracks beneath them.

Primarily using light funk and hip-hop rhythms, with dashes of guitar and

other instruments. DiFranco created a completely different musical

context for Phillips' words while preserving their soul--making a sort of

end run around people's stereotypes of folk music.

"It was a very calculated move on my part," says DiFranco,

"because I can see people around me, people my age, who haven't had the

experience I have of being thrown into folk festivals half their lives and

coming into contact with all this crazy, subcorporate music. I think that

they'd be people who'd see Utah and think, 'What is this? He looks like

Santa Claus, he's sitting on a stool with an acoustic guitar, and he's

singing, what, labor songs? This has nothing to do with me. I don't

think so. No--see ya.' They would never find out that what he has to say

*does* have something to do with them. So [the album] was taking Utah and

putting him into a different context that somebody my age *does* have a

vocabulary for, and then getting them to hear what he has to say."

For his part, Phillips confesses that when DiFranco originally

proposed the project, he had no idea what the result might be like. So,

did the radically new medium for his message come as a shock? "I thought

it was marvelous," Phillips says. "If I were to pick stories that I

wanted to persist if I weren't around, those are the ones I would pick.

Not only that, but she has put them in the right order. That's real

judgement, almost instinctive. I have old folk-music friends, older

people, who say, 'Gee, I wish your voice was louder and the music was

softer.' I just say, 'Hey, this wasn't made for you.'" He adds with a

laugh, "Sometimes it's hard for people to believe that there's something

in the world that wasn't made for them."

The stories collected on 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere' are amazing

creations--folksy and literary at the same time, alternatively playful,

piercing, mischievous, and nostalgic. A true wordsmith, Phillips is

always up to more than he lets on. "I always believed that what happened

between the songs was as important as the songs," he says. "I put a lot

of time into the stories, so that people would laugh and we would share

absurdities together; and I would create this little, narrow window where

I could deal with the labor movement, where I could deal with pacifism,

whatever it was that I was there to do--my agenda--without being

ghettoized as a political performer.

"You talked to me in one of your letters about it," he says to

DiFranco. "You said, 'I understand the use of humor in performance.

You've got to get people laughing so their throats open up wide enough to

be able to swallow something bigger.' That struck me. First of all, it's

funny, and it's a very true thing to say."

The process by which DiFranco married Phillips' words with music

was entirely improvisational. "I would start with the story," she says,

"I would find the BPM [beats per minute] of the story and try to negotiate

a rhythm track to it, and then I would usually start with the bass. I've

got an old Fender P. [Precision] bass. I would come up with a bass line

and then build on top of that." From story to story, DiFranco's music

varies to match the mood. For the lighthearted satire of "Nevada City,

California," she set up Phillips' punch lines with stop-and-start funk

rhythms, as in an old 'Laugh-In' sketch. In the elegiac "Half a Ghost

Town," the music pares down to a slow, sad melody played on a tenor

guitar. One of the most haunting moments comes in "Korea," when the sound

of Phillips tuning his guitar--one of the few appearances of his guitar on

the record--becomes a ghostly melody floating above the looping beat.

"The sound of him tuning the guitar became this kind of trance to me,"

says DiFranco. "I sampled that bit of tuning and sort of made the melodic

structure around that."

_______________

It's impossible to listen to the words of Utah Phillips without

conjuring an image of him on stage: the raconteur and folk historian,

singing and strumming and spinning yarns for an audience. The tradition

of folk music he carries on has a clear public purpose--it's really

inconceivable without an audience. This would seem to be a major

difference between him and DiFranco, who was born into the

singer-songwriter age, which values introspection over social commentary

and writing your own songs over learning any tradition. But here, again,

appearances are deceiving.

"I don't think with either one of us it's either/or," says

Phillips of the contrast between outward-looking and inward-looking music.

"It flows back and forth as a pulse, as a sensibility. Woody Guthrie

wrote, 'When I was walking that endless highway'--there's a lot of 'I' in

Woody. Even when he was writing about someone else, he would still

transpose it into the first person, as he took these journeys into

himself. I can't fault that and say that's primarily ego-driven. What I

think you're talking about is music which *is* ego-driven, what you would

call journal-entry songwriting. That's not what Ani does, the way that I

hear it. I know that's not what I do, [which is to] let people know that

I'm alive and present, and this is how I'm authentically perceiving and

thinking, but to expand it to the point where it can take in a lot of what

other people are experiencing."

"That whole introspective singer-songwriter thing has been kind of

foisted on me," DiFranco adds. "Some people perceive what I do in that

way because I write songs through my own experience. But whenever people

say, 'Well, your work is very confessional,' I say, 'It's no confessional.

I'm not confessing anything. I haven't sinned. These are not my secrets.

This is just my life; this is the stuff I've seen, the stuff I did, and

what I thought about.' There are different ways of speaking your

political perceptions, and it may be [talking about] an event that

occurred in your life or an event that occurred in your town... but each

is a valid path to a certain realization. I think that what we both do is

very much about our small, little epiphanies along the way, moments of

connection between things."

The introspective tag, DiFranco feels, is often mistakenly applied

to the work of women songwriters. "Women have not been all that

instrumental in making and running governments and business," she says,

"and when we sing our labor songs, it's like, we're at home. In a

historical perspective, women's politics exist more in terms of human

interrelationships, which is what we've been assigned to take care of in

society. People look at a chick singing about her abortion or her

relationships and think, 'Oh, that's hyperconfessional, personal,' but to

me it's all political. It's all related."

To DiFranco and Phillips, performing music is all about making

that connection between the individual and the group. "When Utah's

singing a labor song," she says, "the people who work in that town are

coming up and saying, 'Yeah, me too. I can't believe you said that.'"

"Yeah, you get that too," Phillips responds.

"Absolutely," says DiFranco. "Except for me, I'm up there singing

my songs, and who comes up? It's young women in droves: 'Yeah, I can't

believe you said that.' It's the same thing: giving voice to different

groups of people."

_______________

Utah Phillips takes his role as a community voice very seriously.

In fact, he's made a life's work of learning music and stories from

people, starting back in the early '50s with a job on a road crew and some

songs by Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Snow. "The guys on the road crew were

the ones who taught me to play the guitar and sing those songs," he says.

"But it turned out that the songs weren't the important part--the people

who taught them to me were the important part. I can't remember those

songs, but I can remember those people."

When DiFranco was first delving into music as a kid in the '70s,

the typical way to learn was through recordings, copping songs and licks

from pop LPs. Was this her experience? Not at all, she says. "I

definitely learned how to play guitar from people. My parents didn't have

a record player, so my whole experience with music was made by people in

the room for most of my formative years. Luckily for me, there were

always a lot of people around playing guitar, and so [music] has always

been something you *did*, not something you *bought*. I didn't idolize

rock stars; I just had friends who were teaching me songs.

Perhaps because of her record-free childhood, DiFranco also never

adopted the common belief that recording is the most important work of a

professional musician, and that performing is a secondary consideration.

Phillips notes, "Too many young people are getting that backwards, that

somehow a recording history is going to make a living for you. It's not.

What would Bob Feldman from Red House Records tell you, or Ken [Irwin]

from Rounder? They'd say, 'For us to put out a record of you, you've got

to be doing at least 100 dates a year. Otherwise it's not worth it."

DiFranco says, "Kids come up to me, and they want advice about

what's the magic formula to get the national tours and the distribution.

You can see they want, want, want all these things. And I think, 'Maybe

you should just try to get a *gig*. And then maybe you should do that

every weekend for ten years, and then see if you're not on a haphazard

national tour that grew organically and if you don't have some recordings

that you made along the way that are distributed through the people you

encountered along the way."

"What's the work of a poet?" Phillips adds. "To write poetry.

What's the work of an artist? To paint. What's the work of a singer? To

sing. I tell them, 'Fasten totally on the work. Give yourself completely

to the work, till you can do it as well as it can be done, and then people

will come looking for you. But forget the rest of it. That will happen

if you're completely fixed on the work.'"

There's a rich irony behind this whole discussion of recording:

Difranco's and Phillips' collaboration would never have happened without

it. 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere' is a studio-created illusion, a

technological bridge between far-distant musical styles. Only once have

they tried to perform together, on the public-radio show E-Town, and they

have spent much less time together than a spin of their record might

suggest. Plus, individually, they *are* recording artists; DiFranco in

particular has been making records at a breakneck pace--ten solo releases

in seven years. If, as she suggests, the fixation on recordings and

product is one of the main characteristics of commerical music that

distinguish it from folk music like hers and Phillips', how do these two

deal in the record business without losing touch with the wellsprings of

their music?

The answer is unanimous: by maintaining a fiercely independent

stance vis-a-vis the corporate music business. That's a serious

understatement when referring to a man who is fond of saying things like,

"Capitalism is a criminal conspiracy to divest those who do the work of

the wealth that they create," and a woman who sings (no, *screams*), "I'm

the million you never made" and has become the poster child for DIY

musicians. Still, I decide to play devil's advocate and ask them:

couldn't you deliver the same messages that you put out there as a

performer now while being part of the corporate music world?

"Not a chance," says Phillips. "It would destroy your soul. I

would rather sleep under a railroad bridge than work for these assholes.

No, sir, you've got to own the means of production. You've got to own

what you do.

"People my age find folk music very uncool--it's just terribly,

terribly uncool," says Ani DiFranco. With her cropped, green hair, boy's

hockey jersey, collarbone tattoo, and spiked leather jacket with a sticker

on the back that says "Mean People Suck," DiFranco hardly looks like most

people's idea of a folkie--and her edgy, often frenetic music doesn't

sound much like most people's idea of folk, either. So what is she doing

here in Toronto at the Folk Alliance conference, an annual gathering of

the faithful presided over by such archetypal folksingers as Pete Seeger?

DiFranco is here because she has her own definition of the f word. "Folk

music is not an acoustic guitar--that's not where the heart of it is," she

says. "I use the word 'folk' in reference to punk music and rap music.

It's an attitude, it's an awareness of one's heritage, and it's a

community. It's subcorporate music that gives voice to different

communities and their struggle against authority."

The fact that DiFranco defines folk by its spirit and intent

rather than its sound and dress code goes a long way toward explaining

her connection with Utah Phillips, the venerable singer and storyteller

who sits next to her in this hotel ballroom. From his fedora and

snow-white beard to his repertoire of labor songs and populist anthems,

Phillips is as unambiguously a folksinger as he could be--and as

stylistically distant from DiFranco as he could be. But appearances are

deceiving. Just a few hours ago, DiFranco helped present Phillips with

Folk Alliance's Lifetime Achievement Award, citing his gift for entwining

humor, entertainment, and politics as an inspiration for her own music.

This is only one of the many traits and passions they share; their

connection is so strong, in fact, that he's the first outside artist

DiFranco has brought onto the roster of her own Righteous Babe Records

label.

DiFranco's and Phillips' 1996 album for Righteous Babe, 'The Past

Didn't Go Anywhere,' is much more than a unique collaboration between a

folk elder and a rising young star; it's a bold and ambitious musical

statement, brilliantly executed. DiFranco sifted through 100 hours of

Phillips' live tapes and picked a handful of her favorite between-song

raps--the ones that, she says, "made me fall off my chair laughing or

just go off in the corner and cry and mull things over a while." She then

took those stories--chronicling Phillips' desertion from the army during

the Korean War, the mentors who taught him about politics and life, and

various philosophical observations from his years on the road and

rail--and holed up in an Austin studio to layer music tracks beneath them.

Primarily using light funk and hip-hop rhythms, with dashes of guitar and

other instruments. DiFranco created a completely different musical

context for Phillips' words while preserving their soul--making a sort of

end run around people's stereotypes of folk music.

"It was a very calculated move on my part," says DiFranco,

"because I can see people around me, people my age, who haven't had the

experience I have of being thrown into folk festivals half their lives and

coming into contact with all this crazy, subcorporate music. I think that

they'd be people who'd see Utah and think, 'What is this? He looks like

Santa Claus, he's sitting on a stool with an acoustic guitar, and he's

singing, what, labor songs? This has nothing to do with me. I don't

think so. No--see ya.' They would never find out that what he has to say

*does* have something to do with them. So [the album] was taking Utah and

putting him into a different context that somebody my age *does* have a

vocabulary for, and then getting them to hear what he has to say."

For his part, Phillips confesses that when DiFranco originally

proposed the project, he had no idea what the result might be like. So,

did the radically new medium for his message come as a shock? "I thought

it was marvelous," Phillips says. "If I were to pick stories that I

wanted to persist if I weren't around, those are the ones I would pick.

Not only that, but she has put them in the right order. That's real

judgement, almost instinctive. I have old folk-music friends, older

people, who say, 'Gee, I wish your voice was louder and the music was

softer.' I just say, 'Hey, this wasn't made for you.'" He adds with a

laugh, "Sometimes it's hard for people to believe that there's something

in the world that wasn't made for them."

The stories collected on 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere' are amazing

creations--folksy and literary at the same time, alternatively playful,

piercing, mischievous, and nostalgic. A true wordsmith, Phillips is

always up to more than he lets on. "I always believed that what happened

between the songs was as important as the songs," he says. "I put a lot

of time into the stories, so that people would laugh and we would share

absurdities together; and I would create this little, narrow window where

I could deal with the labor movement, where I could deal with pacifism,

whatever it was that I was there to do--my agenda--without being

ghettoized as a political performer.

"You talked to me in one of your letters about it," he says to

DiFranco. "You said, 'I understand the use of humor in performance.

You've got to get people laughing so their throats open up wide enough to

be able to swallow something bigger.' That struck me. First of all, it's

funny, and it's a very true thing to say."

The process by which DiFranco married Phillips' words with music

was entirely improvisational. "I would start with the story," she says,

"I would find the BPM [beats per minute] of the story and try to negotiate

a rhythm track to it, and then I would usually start with the bass. I've

got an old Fender P. [Precision] bass. I would come up with a bass line

and then build on top of that." From story to story, DiFranco's music

varies to match the mood. For the lighthearted satire of "Nevada City,

California," she set up Phillips' punch lines with stop-and-start funk

rhythms, as in an old 'Laugh-In' sketch. In the elegiac "Half a Ghost

Town," the music pares down to a slow, sad melody played on a tenor

guitar. One of the most haunting moments comes in "Korea," when the sound

of Phillips tuning his guitar--one of the few appearances of his guitar on

the record--becomes a ghostly melody floating above the looping beat.

"The sound of him tuning the guitar became this kind of trance to me,"

says DiFranco. "I sampled that bit of tuning and sort of made the melodic

structure around that."

_______________

It's impossible to listen to the words of Utah Phillips without

conjuring an image of him on stage: the raconteur and folk historian,

singing and strumming and spinning yarns for an audience. The tradition

of folk music he carries on has a clear public purpose--it's really

inconceivable without an audience. This would seem to be a major

difference between him and DiFranco, who was born into the

singer-songwriter age, which values introspection over social commentary

and writing your own songs over learning any tradition. But here, again,

appearances are deceiving.

"I don't think with either one of us it's either/or," says

Phillips of the contrast between outward-looking and inward-looking music.

"It flows back and forth as a pulse, as a sensibility. Woody Guthrie

wrote, 'When I was walking that endless highway'--there's a lot of 'I' in

Woody. Even when he was writing about someone else, he would still

transpose it into the first person, as he took these journeys into

himself. I can't fault that and say that's primarily ego-driven. What I

think you're talking about is music which *is* ego-driven, what you would

call journal-entry songwriting. That's not what Ani does, the way that I

hear it. I know that's not what I do, [which is to] let people know that

I'm alive and present, and this is how I'm authentically perceiving and

thinking, but to expand it to the point where it can take in a lot of what

other people are experiencing."

"That whole introspective singer-songwriter thing has been kind of

foisted on me," DiFranco adds. "Some people perceive what I do in that

way because I write songs through my own experience. But whenever people

say, 'Well, your work is very confessional,' I say, 'It's no confessional.

I'm not confessing anything. I haven't sinned. These are not my secrets.

This is just my life; this is the stuff I've seen, the stuff I did, and

what I thought about.' There are different ways of speaking your

political perceptions, and it may be [talking about] an event that

occurred in your life or an event that occurred in your town... but each

is a valid path to a certain realization. I think that what we both do is

very much about our small, little epiphanies along the way, moments of

connection between things."

The introspective tag, DiFranco feels, is often mistakenly applied

to the work of women songwriters. "Women have not been all that

instrumental in making and running governments and business," she says,

"and when we sing our labor songs, it's like, we're at home. In a

historical perspective, women's politics exist more in terms of human

interrelationships, which is what we've been assigned to take care of in

society. People look at a chick singing about her abortion or her

relationships and think, 'Oh, that's hyperconfessional, personal,' but to

me it's all political. It's all related."

To DiFranco and Phillips, performing music is all about making

that connection between the individual and the group. "When Utah's

singing a labor song," she says, "the people who work in that town are

coming up and saying, 'Yeah, me too. I can't believe you said that.'"

"Yeah, you get that too," Phillips responds.

"Absolutely," says DiFranco. "Except for me, I'm up there singing

my songs, and who comes up? It's young women in droves: 'Yeah, I can't

believe you said that.' It's the same thing: giving voice to different

groups of people."

_______________

Utah Phillips takes his role as a community voice very seriously.

In fact, he's made a life's work of learning music and stories from

people, starting back in the early '50s with a job on a road crew and some

songs by Jimmie Rodgers and Hank Snow. "The guys on the road crew were

the ones who taught me to play the guitar and sing those songs," he says.

"But it turned out that the songs weren't the important part--the people

who taught them to me were the important part. I can't remember those

songs, but I can remember those people."

When DiFranco was first delving into music as a kid in the '70s,

the typical way to learn was through recordings, copping songs and licks

from pop LPs. Was this her experience? Not at all, she says. "I

definitely learned how to play guitar from people. My parents didn't have

a record player, so my whole experience with music was made by people in

the room for most of my formative years. Luckily for me, there were

always a lot of people around playing guitar, and so [music] has always

been something you *did*, not something you *bought*. I didn't idolize

rock stars; I just had friends who were teaching me songs.

Perhaps because of her record-free childhood, DiFranco also never

adopted the common belief that recording is the most important work of a

professional musician, and that performing is a secondary consideration.

Phillips notes, "Too many young people are getting that backwards, that

somehow a recording history is going to make a living for you. It's not.

What would Bob Feldman from Red House Records tell you, or Ken [Irwin]

from Rounder? They'd say, 'For us to put out a record of you, you've got

to be doing at least 100 dates a year. Otherwise it's not worth it."

DiFranco says, "Kids come up to me, and they want advice about

what's the magic formula to get the national tours and the distribution.

You can see they want, want, want all these things. And I think, 'Maybe

you should just try to get a *gig*. And then maybe you should do that

every weekend for ten years, and then see if you're not on a haphazard

national tour that grew organically and if you don't have some recordings

that you made along the way that are distributed through the people you

encountered along the way."

"What's the work of a poet?" Phillips adds. "To write poetry.

What's the work of an artist? To paint. What's the work of a singer? To

sing. I tell them, 'Fasten totally on the work. Give yourself completely

to the work, till you can do it as well as it can be done, and then people

will come looking for you. But forget the rest of it. That will happen

if you're completely fixed on the work.'"

There's a rich irony behind this whole discussion of recording:

Difranco's and Phillips' collaboration would never have happened without

it. 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere' is a studio-created illusion, a

technological bridge between far-distant musical styles. Only once have

they tried to perform together, on the public-radio show E-Town, and they

have spent much less time together than a spin of their record might

suggest. Plus, individually, they *are* recording artists; DiFranco in

particular has been making records at a breakneck pace--ten solo releases

in seven years. If, as she suggests, the fixation on recordings and

product is one of the main characteristics of commerical music that

distinguish it from folk music like hers and Phillips', how do these two

deal in the record business without losing touch with the wellsprings of

their music?

The answer is unanimous: by maintaining a fiercely independent

stance vis-a-vis the corporate music business. That's a serious

understatement when referring to a man who is fond of saying things like,

"Capitalism is a criminal conspiracy to divest those who do the work of

the wealth that they create," and a woman who sings (no, *screams*), "I'm

the million you never made" and has become the poster child for DIY

musicians. Still, I decide to play devil's advocate and ask them:

couldn't you deliver the same messages that you put out there as a

performer now while being part of the corporate music world?

"Not a chance," says Phillips. "It would destroy your soul. I

would rather sleep under a railroad bridge than work for these assholes.

No, sir, you've got to own the means of production. You've got to own

what you do.

"If you create it, you're not going to wait around for some big

company to sign you to a label. [To DiFranco] You created a label. Kate

Wolf did that when she created Owl Records. She didn't wait around to be

invited to a folk festival, she created one--the Sonoma Folk Festival.

You don't wait around for these people to acknowledge you. Meanwhile,

sure, you make less, you learn to live cheap, you really learn to find

your wants and needs in a sensible fashion. It's like an indentured

servant buying himself out from indenture, from capitalism. *But*, at a

subindustrial level, you make all the artistic decisions--not the people

in the front office who try to shape your image--and that's what keeps the

material flowing and fresh. When you give into their system, when you

become a bought person and they're going to give you wealth, power, and

fame, and the creative decisions are being made more and more by the

people in the front office, all you can write about is your personal sense

of alienation. You think over the careers of the singer-songwriters of

the '60s and '70s, and that's what you hear."

"And what you have to say will become, without a doubt,

systematically watered down to be more radio-friendly and to be more

accessible," DiFranco adds. "They come up with all kinds of convincing

arguments about why you should adjust your image or why you should play

*this* song every time you appear on TV and water down any kind of

political implications in your music, so that you can be accessible and

make the biggest buck."

Take control and take responsibility: this credo runs deep in

DiFranco and Phillips, guiding much more than just their careers. It's a

philosophy of life that Phillips traces to his mentor Ammon Hennacy,

described on 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere' as a "Catholic, anarchist,

pacifist, draft dodger of two world wars, tax refuser, vegetarian, one-man

revolution in America." Phillips says, "My body is my ballot, and I try

to cast it on behalf of the people around me every day of my life. I

don't assign responsibility to do things to other people; I accept the

responsibility to make sure that things get done. I love to tell that to

people who are frustrated with the ballot box. How many people do I know

who have never voted for anyone who won, ever in their lives, and are

really frustrated? It's not the end of the road. There's another way to

go, and that's with your own labor, your own sweat, your own body. I

think there' a lot of hope in that."

_______________

In the liner notes to 'The Long Memory' the 1996 album by Phillips

and Rosalie Sorrels, he wrote, "The long memory is the most radical idea

in the country. It is the loss of that long memory which deprives our

people of that connective flow of thoughts and events that clarifies our

vision, not of where we're going but where we want to go." As a

performer, Phillips' mission is to be a vehicle for that memory, a means

by which important ideas, stories, and aspirations are passed from

generation to generation. "I'm just a folksinger," he says, "but I have a

real thorough understanding of what that means. Growing up, really

growing up, means at some point in your life discovering what you

authentically inherit, what you culturally inherit. You finally recognize

that, and that's what you try to put in the world. And that's what I do

now. I find that my inheritance is a wealth of song and story and poem

from my elders--especially the radical elders, who never had that wide a

voice in their lives."

In creating 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere,' DiFranco aims to be

another link in that chain. "The pop music realm has a huge disrespect

for our elders," she says. "It's all about worshipping youth. Youth has

a lot of energy, and there's a lot of important shit that goes down in

youth culture, but I don't think that means you ignore your elders or

where you come from. People may constantly want to be inventing the new

alternative, which so quickly gets co-opted and turned into just a

cookie-cutter formula, with just a slightly more distorted guitar or

something, whereas they might be ignoring the fact that they could take

the same old tools--an acoustic guitar--and be working in an old, crusty

medium like folk music, and do something totally new.

"Like Utah would say, 'Shut up and listen to what came before you

and see what use it has.'"

"If you create it, you're not going to wait around for some big

company to sign you to a label. [To DiFranco] You created a label. Kate

Wolf did that when she created Owl Records. She didn't wait around to be

invited to a folk festival, she created one--the Sonoma Folk Festival.

You don't wait around for these people to acknowledge you. Meanwhile,

sure, you make less, you learn to live cheap, you really learn to find

your wants and needs in a sensible fashion. It's like an indentured

servant buying himself out from indenture, from capitalism. *But*, at a

subindustrial level, you make all the artistic decisions--not the people

in the front office who try to shape your image--and that's what keeps the

material flowing and fresh. When you give into their system, when you

become a bought person and they're going to give you wealth, power, and

fame, and the creative decisions are being made more and more by the

people in the front office, all you can write about is your personal sense

of alienation. You think over the careers of the singer-songwriters of

the '60s and '70s, and that's what you hear."

"And what you have to say will become, without a doubt,

systematically watered down to be more radio-friendly and to be more

accessible," DiFranco adds. "They come up with all kinds of convincing

arguments about why you should adjust your image or why you should play

*this* song every time you appear on TV and water down any kind of

political implications in your music, so that you can be accessible and

make the biggest buck."

Take control and take responsibility: this credo runs deep in

DiFranco and Phillips, guiding much more than just their careers. It's a

philosophy of life that Phillips traces to his mentor Ammon Hennacy,

described on 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere' as a "Catholic, anarchist,

pacifist, draft dodger of two world wars, tax refuser, vegetarian, one-man

revolution in America." Phillips says, "My body is my ballot, and I try

to cast it on behalf of the people around me every day of my life. I

don't assign responsibility to do things to other people; I accept the

responsibility to make sure that things get done. I love to tell that to

people who are frustrated with the ballot box. How many people do I know

who have never voted for anyone who won, ever in their lives, and are

really frustrated? It's not the end of the road. There's another way to

go, and that's with your own labor, your own sweat, your own body. I

think there' a lot of hope in that."

_______________

In the liner notes to 'The Long Memory' the 1996 album by Phillips

and Rosalie Sorrels, he wrote, "The long memory is the most radical idea

in the country. It is the loss of that long memory which deprives our

people of that connective flow of thoughts and events that clarifies our

vision, not of where we're going but where we want to go." As a

performer, Phillips' mission is to be a vehicle for that memory, a means

by which important ideas, stories, and aspirations are passed from

generation to generation. "I'm just a folksinger," he says, "but I have a

real thorough understanding of what that means. Growing up, really

growing up, means at some point in your life discovering what you

authentically inherit, what you culturally inherit. You finally recognize

that, and that's what you try to put in the world. And that's what I do

now. I find that my inheritance is a wealth of song and story and poem

from my elders--especially the radical elders, who never had that wide a

voice in their lives."

In creating 'The Past Didn't Go Anywhere,' DiFranco aims to be

another link in that chain. "The pop music realm has a huge disrespect

for our elders," she says. "It's all about worshipping youth. Youth has

a lot of energy, and there's a lot of important shit that goes down in

youth culture, but I don't think that means you ignore your elders or

where you come from. People may constantly want to be inventing the new

alternative, which so quickly gets co-opted and turned into just a

cookie-cutter formula, with just a slightly more distorted guitar or

something, whereas they might be ignoring the fact that they could take

the same old tools--an acoustic guitar--and be working in an old, crusty

medium like folk music, and do something totally new.

"Like Utah would say, 'Shut up and listen to what came before you

and see what use it has.'"

Special thanx to Gary for typin this all up!

Back to Article and Review Land