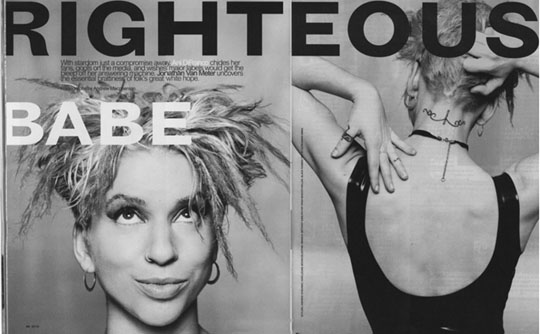

Righteous Babe

With Stardom just a compromise away, Ani DiFranco chides her fans,

goofs off on the media and wishes major labels would get the bleep off

her answering machine. Jonathan Van Meter uncovers the essential

brattiness of folks great white hope.

Tonight in Knoxville, Ani DiFranco is onstage at the Tennessee

Theater doing one of the two things she does best: talking. She is

talking to her audience, her fans, and oh, what fanatics they are.

Pierced, tattooed, obsessed, sexually ambiguous, passionate, young,

noisy, bossy, possessive, and demanding, DiFranco's hair id dyed

magenta, her T-shirt is orange, her skintight latex pants are electric lime

green. She has never performed here before, and whenever she plays a

new town - what her her manager calls "breaking in a new market" - it

feels a little bit like she's gone back in time a couple of years, when her

audiences were mostly women. New markets always bring out the

original, hardcore fans: the dykes.

In a few minutes she will start doing the other thing she does best:

making music. She will sing a song that she's just recently written. A

song that goes, in part, like this: [from little plastic castle]

From the shape of your shaved head

I recognize your silhouette

As you walked out of the sun, and sat down

And the sight of your sleepy smile

Eclipsed all [the] other people

As they paused to sneer at the two girls

From out of town

The Dykes in the audience will love this song. They will feel validated

by it, and why not? It's classic Ani DiFranco. Who else writes songs

about sleepy, smiling bald headed girls in a coffee shop, in a small

town, getting hostile glances from the locals?

The dykes will feel that this song is about them. What's not clear,

though, is if they will follow the song to it's slightly irritated

conclusion, and realize that it is, quite literally, a song about them

People talk

About my image

Like I come in two dimensions

Like lipstick, is a sign of my declining mind

Like what I happen to be wearing

The day that someone takes a picture

Is my statement for all womankind ...

But I'm getting ahead of myself. She hasn't sung this song yet. She's

still talking. "It's a girl vibe! It's like, a pitch thing!" She does an

imitation of the roar of a mixed-gender crowd of a girl crowd.

Then she singles out a guy in the front row. "You are a brave man.

There is, like one fucking sensitive beautiful, brave man in the

audience" Someone shouts out, "Men are pigs!!" and DiFranco brings

the proceedings to a grinding halt.

"One thing I hate...m" she says, quietly seething. The room falls

silent. Her voice rises an octave and into the tone, if not the syntax, of

a grade-school teacher admonishing her pupils. "You know, it's really

nice to be, like, in the groove of a girl vibe, because there's a feeling of

strength, but I so want there to be feeling of inclusion. There's a lot of

sad shit that goes down in my songs, that goes down in my world and

my life, bit I never think of it as an us vs. them situation.

The energy has been sucked up right out of the room. A few songs

latter, she talks some more. "I was is New York at a traumatic photo

shoot. They kind of go from mildly traumatic to absolutely

devastating. It always starts with a dress"

She imitates a gay male stylist "Oh, you would look exquisite in this!"

I put it on, and it's see through. And I'm like, "Uhmm ... uhm ..." She

fiddles with her guitar, pauses for effect. "It was Jugs magazine, so I

don't know why I was fighting it"

The audience roars with laughter and finally, the bond, the connection,

the love, returns.

The next day, in a rock club in Birmingham, Alabama, DiFranco is

hanging out in her dressing room with candles burning all around her,

all the lights soft, waiting for showtime. It occurs to me that in addition

to the pressure from the image-making machinery to wear see-through

gowns, Ani DiFranco is getting the exact opposite pressure from the

other end of the spectrum: the dyke fans and the gender-identity

political freaks who feel betrayed is she isn't wearing pants - like

lipstick is a sign of her declining mind.

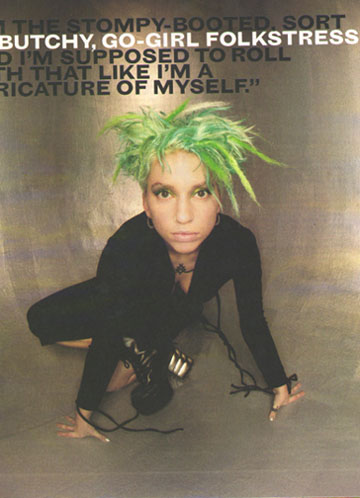

When I share this thought she lets loose with frustration and

defensiveness. "like I'm supposed to have hammered out this niche for

myself now. I'm the stompy-booted, sort of butchy, Go-girl folkstress,

and I'm supposed to just roll with that like I'm a caricature of myself..

People try to turn me into my fans, I was thinking that again last night

when that chick yelled out, 'men are pigs' I was thinking 'YOU are

why they stereotype me' All my life I've been the angry man hating,

puppy eating hairy, homely, feminist bitch!"

With Stardom just a compromise away, Ani DiFranco chides her fans,

goofs off on the media and wishes major labels would get the bleep off

her answering machine. Jonathan Van Meter uncovers the essential

brattiness of folks great white hope.

Tonight in Knoxville, Ani DiFranco is onstage at the Tennessee

Theater doing one of the two things she does best: talking. She is

talking to her audience, her fans, and oh, what fanatics they are.

Pierced, tattooed, obsessed, sexually ambiguous, passionate, young,

noisy, bossy, possessive, and demanding, DiFranco's hair id dyed

magenta, her T-shirt is orange, her skintight latex pants are electric lime

green. She has never performed here before, and whenever she plays a

new town - what her her manager calls "breaking in a new market" - it

feels a little bit like she's gone back in time a couple of years, when her

audiences were mostly women. New markets always bring out the

original, hardcore fans: the dykes.

In a few minutes she will start doing the other thing she does best:

making music. She will sing a song that she's just recently written. A

song that goes, in part, like this: [from little plastic castle]

From the shape of your shaved head

I recognize your silhouette

As you walked out of the sun, and sat down

And the sight of your sleepy smile

Eclipsed all [the] other people

As they paused to sneer at the two girls

From out of town

The Dykes in the audience will love this song. They will feel validated

by it, and why not? It's classic Ani DiFranco. Who else writes songs

about sleepy, smiling bald headed girls in a coffee shop, in a small

town, getting hostile glances from the locals?

The dykes will feel that this song is about them. What's not clear,

though, is if they will follow the song to it's slightly irritated

conclusion, and realize that it is, quite literally, a song about them

People talk

About my image

Like I come in two dimensions

Like lipstick, is a sign of my declining mind

Like what I happen to be wearing

The day that someone takes a picture

Is my statement for all womankind ...

But I'm getting ahead of myself. She hasn't sung this song yet. She's

still talking. "It's a girl vibe! It's like, a pitch thing!" She does an

imitation of the roar of a mixed-gender crowd of a girl crowd.

Then she singles out a guy in the front row. "You are a brave man.

There is, like one fucking sensitive beautiful, brave man in the

audience" Someone shouts out, "Men are pigs!!" and DiFranco brings

the proceedings to a grinding halt.

"One thing I hate...m" she says, quietly seething. The room falls

silent. Her voice rises an octave and into the tone, if not the syntax, of

a grade-school teacher admonishing her pupils. "You know, it's really

nice to be, like, in the groove of a girl vibe, because there's a feeling of

strength, but I so want there to be feeling of inclusion. There's a lot of

sad shit that goes down in my songs, that goes down in my world and

my life, bit I never think of it as an us vs. them situation.

The energy has been sucked up right out of the room. A few songs

latter, she talks some more. "I was is New York at a traumatic photo

shoot. They kind of go from mildly traumatic to absolutely

devastating. It always starts with a dress"

She imitates a gay male stylist "Oh, you would look exquisite in this!"

I put it on, and it's see through. And I'm like, "Uhmm ... uhm ..." She

fiddles with her guitar, pauses for effect. "It was Jugs magazine, so I

don't know why I was fighting it"

The audience roars with laughter and finally, the bond, the connection,

the love, returns.

The next day, in a rock club in Birmingham, Alabama, DiFranco is

hanging out in her dressing room with candles burning all around her,

all the lights soft, waiting for showtime. It occurs to me that in addition

to the pressure from the image-making machinery to wear see-through

gowns, Ani DiFranco is getting the exact opposite pressure from the

other end of the spectrum: the dyke fans and the gender-identity

political freaks who feel betrayed is she isn't wearing pants - like

lipstick is a sign of her declining mind.

When I share this thought she lets loose with frustration and

defensiveness. "like I'm supposed to have hammered out this niche for

myself now. I'm the stompy-booted, sort of butchy, Go-girl folkstress,

and I'm supposed to just roll with that like I'm a caricature of myself..

People try to turn me into my fans, I was thinking that again last night

when that chick yelled out, 'men are pigs' I was thinking 'YOU are

why they stereotype me' All my life I've been the angry man hating,

puppy eating hairy, homely, feminist bitch!"

She runs out of steam, trails off, and looks down, as if slightly

embarrassed by the spew of her frustration. "So I guess ... yeah, I

cannot be caricature. But a lot of my fans do want it simple, they want

it easy. And when I insist on my own stupid personality quirks it can

be offensive to them."

Outside, fans are gathering, perhaps a couple hundred, waiting to be let

in. DiFranco goes to surprisingly great lengths to avoid contact with

her fans. She wants to go for a walk before taking the stage tonight, so

she does her best to cover up all visible quirks by wearing a plain

brown pair of Dickies and a baggy blue sweet shirt. She jerks the hood

up over and heads out the stage door. A clean getaway.

Not since Bob Dylan plugged in his electric guitar have a group of fans

been so freaked by an artists evolution. Since 1990 (when, at the ago

of 20, she released her first album, Ani DiFranco, on her own label,

Righteous Babe Records), the tiny, 5'3" DiFranco has been at the

center of a cult of personality that has slowly grown to epic

proportions. She has, quite simply, created a monster.

After several homespun, self-produced releases, filled with overly

political, often funny, sometimes brilliant, and distinctly old-school

feminist songs, DiFranco reached her own apotheosis with the 1995

release Not a Pretty Girl (which sold 112,000 copies). The title track

reads like a mission statement for young feminists everywhere. One

fan I encountered - a member of a white girl gang from Oregon - told

me that "32 flavors," another track, was their team fight song, And

then . . .

Ani DiFranco met a guy, fell in love, grew her hair out, and became a

pretty girl. She even started wearing dresses and lipstick occasionally.

Every song on her next album, Dilate, explored the contours of this

new relationship: love, love/hate, hate. The album garnered her best

reviews to date (it entered the Billboard charts at No. 89 and sold over

174,000 copies), and suddenly DiFranco didn't belong just to the dykes

and the feminists and longer.

RIGHTEOUS BABE, AN INDIE SUCCESS STORY:

Ani DiFranco's label rises up form the grass roots.

This was the headline on the cover of Billboard, April 12, 1997. After

seven years of being her own boss and touring ceaselessly around the

country, after seven years of building a rabidly loyal fan base through

playing small bars, coffeehouses, colleges campuses, and folk festivals,

after seven years if the best grass roots word of mouth wince Bruce

Springstein player the stone pony, Ani DiFranco suddenly popped up

on the radar screen of popular culture.

But it wasn't so much that her music finally caught fire with a larger

audience, or that her potent, confessional lyrics had at once connected

to the mainstream. It was that she was making more money per unit

that Hootie & the Blowfish. And the story had legs. Both the Wall

Street Journal and Time magazine weighed in on the subject. DiFranco

found herself in the surreal position of sitting behind a desk on the

financial news network being asked to prattle on about profit margins.

Forbes magazine even got the Artist Formerly know as Prince - the

major label slave himself, and perhaps the only person alive who

cranks out more music than DiFranco - on the blower for a comment.

"I love Ani DiFranco," he said "She's making four dollars a record and

the superstars are only making two dollars, so who's got the better

deal?"

The music and alternative press have been lavishing praise on

DiFranco's music for a few years now, but since her last two releases

have cracked the billboard charts - this years double live album

Living in Clip debuted at no 59 - the focus has shifted. "Now

suddenly, I'm a brilliant strategist" she says "where I used to be this

stupid girl with too 'tude for her own good, who's is cutting off her

nose to spite her face and the music industry. And everybody would

say "You're selling thousands of albums, and we can help you. Don't

you want people to hear your music?" And it was like "She does an

imitation of Charlie Browns teacher "Wah-Wah-wah-wah"

One of those people was Danny Goldberg, president and CEO of

Mercury Records. He once bragged to a reporter that Righteous Babe

Records never returned his calls. When I talk to him about DiFranco ,

he is quick to put me in ,y place when I suggest that what she is doing,

from a business standpoint, is unique.

"I don't think she's reinventing the wheel," he says, a bit

defensively, "Fugazi did the same thing, Bad Religion did it for years.

It's part of her PR shtick that she has her own label and she makes

more per unit on it, and feels more in control of it. I find that less

interesting. A lot of people have indie labels. There are very few

artists like Ani DiFranco. If she wasn't a good artist and she had her

own label, who'd give a shit?"

She runs out of steam, trails off, and looks down, as if slightly

embarrassed by the spew of her frustration. "So I guess ... yeah, I

cannot be caricature. But a lot of my fans do want it simple, they want

it easy. And when I insist on my own stupid personality quirks it can

be offensive to them."

Outside, fans are gathering, perhaps a couple hundred, waiting to be let

in. DiFranco goes to surprisingly great lengths to avoid contact with

her fans. She wants to go for a walk before taking the stage tonight, so

she does her best to cover up all visible quirks by wearing a plain

brown pair of Dickies and a baggy blue sweet shirt. She jerks the hood

up over and heads out the stage door. A clean getaway.

Not since Bob Dylan plugged in his electric guitar have a group of fans

been so freaked by an artists evolution. Since 1990 (when, at the ago

of 20, she released her first album, Ani DiFranco, on her own label,

Righteous Babe Records), the tiny, 5'3" DiFranco has been at the

center of a cult of personality that has slowly grown to epic

proportions. She has, quite simply, created a monster.

After several homespun, self-produced releases, filled with overly

political, often funny, sometimes brilliant, and distinctly old-school

feminist songs, DiFranco reached her own apotheosis with the 1995

release Not a Pretty Girl (which sold 112,000 copies). The title track

reads like a mission statement for young feminists everywhere. One

fan I encountered - a member of a white girl gang from Oregon - told

me that "32 flavors," another track, was their team fight song, And

then . . .

Ani DiFranco met a guy, fell in love, grew her hair out, and became a

pretty girl. She even started wearing dresses and lipstick occasionally.

Every song on her next album, Dilate, explored the contours of this

new relationship: love, love/hate, hate. The album garnered her best

reviews to date (it entered the Billboard charts at No. 89 and sold over

174,000 copies), and suddenly DiFranco didn't belong just to the dykes

and the feminists and longer.

RIGHTEOUS BABE, AN INDIE SUCCESS STORY:

Ani DiFranco's label rises up form the grass roots.

This was the headline on the cover of Billboard, April 12, 1997. After

seven years of being her own boss and touring ceaselessly around the

country, after seven years of building a rabidly loyal fan base through

playing small bars, coffeehouses, colleges campuses, and folk festivals,

after seven years if the best grass roots word of mouth wince Bruce

Springstein player the stone pony, Ani DiFranco suddenly popped up

on the radar screen of popular culture.

But it wasn't so much that her music finally caught fire with a larger

audience, or that her potent, confessional lyrics had at once connected

to the mainstream. It was that she was making more money per unit

that Hootie & the Blowfish. And the story had legs. Both the Wall

Street Journal and Time magazine weighed in on the subject. DiFranco

found herself in the surreal position of sitting behind a desk on the

financial news network being asked to prattle on about profit margins.

Forbes magazine even got the Artist Formerly know as Prince - the

major label slave himself, and perhaps the only person alive who

cranks out more music than DiFranco - on the blower for a comment.

"I love Ani DiFranco," he said "She's making four dollars a record and

the superstars are only making two dollars, so who's got the better

deal?"

The music and alternative press have been lavishing praise on

DiFranco's music for a few years now, but since her last two releases

have cracked the billboard charts - this years double live album

Living in Clip debuted at no 59 - the focus has shifted. "Now

suddenly, I'm a brilliant strategist" she says "where I used to be this

stupid girl with too 'tude for her own good, who's is cutting off her

nose to spite her face and the music industry. And everybody would

say "You're selling thousands of albums, and we can help you. Don't

you want people to hear your music?" And it was like "She does an

imitation of Charlie Browns teacher "Wah-Wah-wah-wah"

One of those people was Danny Goldberg, president and CEO of

Mercury Records. He once bragged to a reporter that Righteous Babe

Records never returned his calls. When I talk to him about DiFranco ,

he is quick to put me in ,y place when I suggest that what she is doing,

from a business standpoint, is unique.

"I don't think she's reinventing the wheel," he says, a bit

defensively, "Fugazi did the same thing, Bad Religion did it for years.

It's part of her PR shtick that she has her own label and she makes

more per unit on it, and feels more in control of it. I find that less

interesting. A lot of people have indie labels. There are very few

artists like Ani DiFranco. If she wasn't a good artist and she had her

own label, who'd give a shit?"

It's ironic that Goldberg, the man credited with transforming Nirvana

form a local Seattle band into a worldwide phenomenon, would miss

the larger significance of DiFranco's fierce independence. If we are to

believe the mythology of Kurt Cobain's suicide - drug addiction and

depression not withstanding - part of what pushed him to the edge was

that he was embarrassed to be a rock star, At a time when

independence is worn as a mask (witness this years Oscars), and when

otherwise smart talented people sell their art down the river on a daily

basis, DiFranco seems to stand alone, it takes a mighty will to resist the

constant call of corporations when they come along with cash, limos,

and the promise to make you a star. Hardly anyone ever says no. Ani

DiFranco has been saying no to every single major label, week in and

week out, for a couple of years now. "They don't have anything I

want" she says.

I ask DiFranco about the call of the music industry, "Why conquer the

world?" she shoots back "I was thinking about that band today, on of

those new, white blooded, 12-year-old bands. Hanson? NO, not them.

Radish. Some young young boy. Here you have a kid that can maybe

hold a tune, can write verse-chord-verse, talented. That's the death of

him. Give him 10 years. Leave him alone."

The idea of pacing yourself and developing at a realistic rate as an artist

seems to be lost as a virtue in our culture. The seizing of fame and

money - not connecting with and building a true and natural audience

- has become the goal for many artists today. DiFranco is an example

of how to be truly, unpretentiously independent and successful.

"The idea of being a rock star is adolescent fantasy" she says. "And the

idea of being a working musician is a fucking job. It's work. And it

takes a lot of real decisive calculation in terms of holding yourself

back. Consciously holding yourself back. Not just me but Scott

fisher, my manager, who runs the records company. When we get an

offer to do a TV spot, we actually say no. We do crazy shit"

And her fans don't miss a trick. When DiFranco allowed an MTV

crew to film her onstage during a performance in 1995, a fan yelled

"MTV Sucks! What are they doing here?" Tabitha Soren wrote about

the experience afterwards. "I have never come into contact with such

protective - to the point of possessive - fans as DiFranco's. I realize

that an awkward position I put her in."

This may be the first time in history that a journalist publicly

apologized for merely existing. DiFranco even brings out the protective

and possessive in the media.

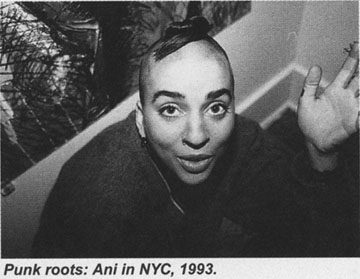

Having played a guitar onstage in bars since the ago of nine could have

turned Ani DiFranco into the Shirley Temple of folk music, but instead

she became it's Jodie Foster. She was born September 23, 1970, In

Buffalo, New York, to Elizabeth and Dante DiFranco. Both parents

graduated from MIT. Dad became a research engineer, Mom an

architect. Elizabeth was one of only a few women in her class, and

rode a motorcycle as a young woman.

DiFranco has said that life at home with her parents and older brother

was "like one scary scene after another" Her parents separated when

she was 11 "My mother moved out and I went with her" says

DiFranco. "So it was just me and my mother in a little apartment, and

my mother kind of freaked out and became a housecleaner. It was like

she demoted herself."

When Ani was 15, her mother moved to Connecticut; Ani chose to stay

behind in Buffalo and fend for herself, eventually getting her own

apartment and living unofficially as an emancipated minor while she

finished high school. Today, again, she shares a house with her

mother, but it's Ani's house, a big old thing with a front porch and a

pretty little lawn in downtown Buffalo that she bought a couple of

years ago and renovated herself. Her mother is among the nine people

who work for righteous babe records.

Her parents humored her and bought her a little kids guitar when she

was nine. Michael Meldru was working at the guitar store "He was

kind of a Buffalo Personality, folk singer, barfly, small-time promoter,

poet, degenerate, songwriter guy" says DiFranco. "We just hit it off.

I'm nine, he's 30. I was a precocious kid, and maybe one of the few

people who would listen to him, and he was my friend and mentor"

Meldrum once told Ms. Magazine "I saw a little girl with pigtails down

to her knees, and braces. Big Smile, open eyes, a lot of wonder ... she

had a great voice, a big voice coming out of this very little person ..."

He took her out to a bar on her 11th birthday, she got served.

It's no surprise that DiFranco - like so many people of her generation -

is the product of a broken home. She has been playing the adult for so

long, and redefining the meaning of family in her life, that one can't

help but sense her world-weariness. The difference, though, is that

DiFranco is not cynical. She seems to truly love and depend on her

"family" around her - the crew, the band, the label folks.

One day, riding on the tour bus, DiFranco is reading aloud a glowing

review of Living in Clip to Andy Stochansky, her longtime drummer,

and Jason Mercer, her new bass player (replacing Sara Lee, formerly

of Gang of Four) She mocks the reviews verbosity, while clearly

enjoying the fact that it is overwhelmingly positive. "As the foil for

most of DiFranco's onstage jokes and musings" she reads

"[Stochansky] plays a valuable role by affirming that this singular

performer's art isn't just a girl thing" She looks up at Stochansky and

says "Because you have a cock, it adds a while new dimension.

There's a boy on stage. We can all rest assured."

DiFranco is not an angry person, so comments like these aren't

unnerving. She has an essential brattiness that's the key to her appeal.

When she says "Fuck You" It's with a big toothy smile splashed across

her face.

It doesn't take me long to spot the boyfriends: Andrew Gilchrist (aka

the goat boy, because of his strangely appealing, caprina visage) is also

DiFranco's sound engineer. I see that they both wear the same ring.

One of the first things I notice in the Buffalo house is a framed picture

of Gilchrist, just inside the door.

For years, many people assumed DiFranco was a lesbian. When I ask

her how she defines her sexuality, she says that she doesn't. "I'm

attracted to different things that may or may not have to do with

gender. The person that I'm in love with now - the goat boy - the

thing that makes our relationship so perfect is that it's so dubiously

gendered. We take turns. It's supposed to be 'Oh, big righteous babe

falling in love for a man. Boo hiss taboo betrayal' And it's like 'You

should see him! He's more of a girl than I am" we fell in love, and it

was very tortured because we hurt other people that we were with, and

that's the album Dilate, I'm not playing any of those songs now.

I hate forcing labels on people who avoid them, but or the sake of

conversation, DiFranco seems to be, in practice, a male-oriented

bisexual. When I ask her if she's ever been afraid of men, she blurts

out "They're scary! Yeah!" And then backpedals "But it's the way

we're socialized .... I mean, like, people are just scary fucking

monsters!" She laughs uproariously. "I was really young and in the bar

scene and men were very carnivorous. So men terrified me But now in

my life it's the women what are really carnivorous, and really the most

manipulative. It's bizarre. Like I'm standing onstage playing and I

look down and some woman will wag her tongue at me. Or someone

will scream at me 'Play this! Play that! Talk! Sing!' Imagine if it were

men behaving that way. A few nights ago, some women was yelling

'Sing! Sing!' I looked right at her and said. 'Why don't you just have a

child and boss IT around1"

At the show in Birmingham, Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls turns up on

her motorcycle. She and DiFranco are good friends. "We both have

this part of our brain that makes us think that everybody should and

will be nice and friendly and forthcoming" says DiFranco "And then

we're completely disillusioned. We have all these grand plans. One of

them is the Rolling Thunder Pussy Revue. There's all these women's

festivals going on this summer, and we don't think they're as

adventurous as they could be. Lilth Fair - right away, by the name, you

know they aren't pushing the envelope hard enough. "

After the show, DiFranco and Way hand out in the dressing room, and

at one point, start talking about their tattoo's, specifically one way just

got on her chest. She has an appointment in a few days in New York

with Joan Jett's tattoo artist, a woman, to have it fixed. "The guy talked

me into pitting it on my chest and I was going to put in on my back."

Says ray. "I think he was just trying to talk me into taking my shirt off.

I was, like, ' I've been raped by the tattoo man!" They both laugh.

"I got a tattoo from a guy that wax kind of weird" says DiFranco. "This

thing on the back of my neck is basically a prison tattoo: a couple of

squiggly lines, so simple you could do it with a paring knife. And it

was crocked and asymmetrical. And he was not very friendly"

"Did you feel funny afterwards?" asks Ray

"Yup" says DiFranco, "I felt very angry."

"Did you feel violated?"

"Oh totally," says DiFranco. "I was like, 18, isn't that weird?"

says Ray

"That's when I decided I would only go to women" says DiFranco. "But then

the women who did this, I HATED!"

I can't help but notice that Ani DiFranco seems to be experiencing

some kind of ideological shift where gender I concerned. Part of what

has made feminism appealing once again is that you don't have to hate

men to feel truly empowered. Perhaps she's finding, it's too easy and

reactionary to always say that girls are better.

She calls herself the folksinger. As does everyone else in the stage,

tight crew that compromises the DiFranco family traveling circus. As

in "Where's The Folksinger?" That she calls herself the folksinger is of

note because DiFranco is called so many things, self-made,

independent, feminist, bisexual, folk, punk, singer/songwriter, guitar

player, hero, role model, phenomenon.

When I first encountered DiFranco in Knoxville, I told her I had just

been stopped by a cop for no apparent reason and that he felt it

necessary to search my rental for "drugs or guns or anything illegal"

She related a story form her early touring days, when she was traveling

alone with her guitar through Texas one sweltering summer day -

topless. A cop pulled her over, found her half naked with a box of

cash and cassettes in the trunk, and demanded to know what she was

doing and where she was going. She pleaded with the officer "I'm a

folk singer!!"

Birmingham to Tampa, 600 miles. The band and crew, 11 in all, are

hoped-up tonight as the bus takes off at 1 AM "Bus Surfing!" shouts

DiFranco. Blinking X-mas lights are turned on, and a joint is passed

around. Somebody's making blender drinks with fruit and vodka.

System 7 is pumping form the sound system, and suddenly the bus has

been transformed into a rolling disco. All 11 people crowd into the

front lounge and dance like mad, whooping and hollering and trying to

stand up as the huge bus lumbers around curves and corners. DiFranco,

complaining that she can't dance to this particular choice, changes the

music to James Brown. After an hour of bumping and grinding, people

fall out and sit down, one by one.

DiFranco scooches next to me on a banquette. James Brown is still

playing. We are very stoned. "Dig the lyrics to this song" she says

"Stand up Baby, let me see where you're coming form" Obviously a

cry for social action. And then he says "get involved! Get involved!"

He keeps repeating it. Again a cry for social action" At this point we

are practically sitting on top o one another, her face just inches away.

"He's also an environmentalist, " she says half serious "There's that

song 'what do we need? Solar power!" people think he's saying soul

power. But he's actually saying solar power Again a political message

Wow

There are a couple of things about the folksinger that push the

boundaries of folk music. One is that she is deeply funky. On this tour

she has been opening with a very tribe called quest-ish version of a

poem she wrote called "IQ" [myIQ actually] She pulls off a kind of

1990-East-Coast-hip-hop, diggity-diggity rhyme style with amazing

success for a white girl form Buffalo. She is also a great dancer. In her

ever present KISS boots - silver plated clunkers that add a few inches -

she jerks and swivels her body, with an innate rhythm to rival any

current r&b artist.

The other thing about the folksinger that surprises me is that she is so

funny. Her performances veer into such over-the-top giddiness as to

give one the impression that she is half stand up comic. The rhythm of

her between song spiels is more Roseanne than Joan Baez.

Back on the Bus, after the surfing, I say 'rock and roll is rarely funny"

"yeah right, she says, "All my life I've always felt like the most un-cool

person. Because it's not cool to be happy, it's not cool to be funny.

For me, it's just not cool to be boring. I can't take it. So I'd rather

hang out with the class clowns than the cool guys"

The Tampa Bay performing Arts Center, 6 PM. The DiFranco family

Circus has pulled into town, only to discover that they are surrounded

by surreality. In the Holiday Inn next door, where we are staying, a

Narcotics Anonymous convention is in full swing - everywhere you

look there are ex-drug addicts, everyone of them looking like ten miles

of rough trail. In the complex where DiFranco will perform, a Catholic

high school prom is unfolding.

Outside on the loading dock of the convention center, DiFranco, whose

hair is now bleached blonde, pulls me aside. "I was thinking about

something that you said last night, that you didn't expect my show

would be funny. I've always had this basic understanding of what folk

music is, that is has to do with economics, that it is sub-corporate

music. Folk music is not on the radio, folk music does not make

money, folk music is more community based, politically oriented, of

the people. Rock music is more of a commodity.

"But you made me realize that another major distinction between rock

n roll and folk music is humor. What references in rock n roll do you

have for humor? Rock n Roll takes itself so seriously; folk music never

does. Because it's not cool to be funny, It's corny. My new little

manifesto is that folksingers take everything very seriously except for

themselves. They talk about social issues, political issues, , their

country, their society, their lives, their time, their place. But in this

whole rock n roll milieu, you take nothing seriously, save yourself. It's

so self-serious and tortured and grandiose"

This is, of course, an oversimplification, but she has a point. Suddenly,

Stochansky, who plays DiFranco's straight man on stage, gets dragged

into the conversation.

"He didn't say anything for, like, a year" says DiFranco. "I just kept

turning around and verbally abusing him, and eventually he just started

talking. Except he's always get the audience sympathy. They'd all

turn to Andy and go, "awwwwwwww" fucking perfect job in the

universe. Walk out, hit things with sticks, get sympathy from all the

hot babe-age"

The day before, in Alabama, Stochansky and I had gone for a walk

before the show and found a grassy lawn on which to hang out. He is

what a friend of mine called a "SNAG" a sensitive new age guy. He

and DiFranco have been playing together for six years, and the bond is

deep. "She always felt like family" h said, and then recalled the day

DiFranco met his father, a Ukrainian immigrant. "You are a dirty girl"

he said. To which she replied "And someday, I'm going to be a dirty

old woman"

When Stochansky, who is from Toronto, first started playing with

DiFranco, it was just the two of them onstage, and he was often one of

the only men in the room. He told me about the moment things shifted.

"At X-mas, a couple of years ago, in Vancouver. One night , it just

happened. I came back to the dressing room and said 'Ani, you're not

going to believe this, but there are guys out there. Not only that, but

there are probably more straight people than gay people. ' I went from

playing a primarily female gay audience, to suddenly having all these

guys cheer me on. I immediately felt like "No! I don't want to be in

tune with you!"

It's ironic that Goldberg, the man credited with transforming Nirvana

form a local Seattle band into a worldwide phenomenon, would miss

the larger significance of DiFranco's fierce independence. If we are to

believe the mythology of Kurt Cobain's suicide - drug addiction and

depression not withstanding - part of what pushed him to the edge was

that he was embarrassed to be a rock star, At a time when

independence is worn as a mask (witness this years Oscars), and when

otherwise smart talented people sell their art down the river on a daily

basis, DiFranco seems to stand alone, it takes a mighty will to resist the

constant call of corporations when they come along with cash, limos,

and the promise to make you a star. Hardly anyone ever says no. Ani

DiFranco has been saying no to every single major label, week in and

week out, for a couple of years now. "They don't have anything I

want" she says.

I ask DiFranco about the call of the music industry, "Why conquer the

world?" she shoots back "I was thinking about that band today, on of

those new, white blooded, 12-year-old bands. Hanson? NO, not them.

Radish. Some young young boy. Here you have a kid that can maybe

hold a tune, can write verse-chord-verse, talented. That's the death of

him. Give him 10 years. Leave him alone."

The idea of pacing yourself and developing at a realistic rate as an artist

seems to be lost as a virtue in our culture. The seizing of fame and

money - not connecting with and building a true and natural audience

- has become the goal for many artists today. DiFranco is an example

of how to be truly, unpretentiously independent and successful.

"The idea of being a rock star is adolescent fantasy" she says. "And the

idea of being a working musician is a fucking job. It's work. And it

takes a lot of real decisive calculation in terms of holding yourself

back. Consciously holding yourself back. Not just me but Scott

fisher, my manager, who runs the records company. When we get an

offer to do a TV spot, we actually say no. We do crazy shit"

And her fans don't miss a trick. When DiFranco allowed an MTV

crew to film her onstage during a performance in 1995, a fan yelled

"MTV Sucks! What are they doing here?" Tabitha Soren wrote about

the experience afterwards. "I have never come into contact with such

protective - to the point of possessive - fans as DiFranco's. I realize

that an awkward position I put her in."

This may be the first time in history that a journalist publicly

apologized for merely existing. DiFranco even brings out the protective

and possessive in the media.

Having played a guitar onstage in bars since the ago of nine could have

turned Ani DiFranco into the Shirley Temple of folk music, but instead

she became it's Jodie Foster. She was born September 23, 1970, In

Buffalo, New York, to Elizabeth and Dante DiFranco. Both parents

graduated from MIT. Dad became a research engineer, Mom an

architect. Elizabeth was one of only a few women in her class, and

rode a motorcycle as a young woman.

DiFranco has said that life at home with her parents and older brother

was "like one scary scene after another" Her parents separated when

she was 11 "My mother moved out and I went with her" says

DiFranco. "So it was just me and my mother in a little apartment, and

my mother kind of freaked out and became a housecleaner. It was like

she demoted herself."

When Ani was 15, her mother moved to Connecticut; Ani chose to stay

behind in Buffalo and fend for herself, eventually getting her own

apartment and living unofficially as an emancipated minor while she

finished high school. Today, again, she shares a house with her

mother, but it's Ani's house, a big old thing with a front porch and a

pretty little lawn in downtown Buffalo that she bought a couple of

years ago and renovated herself. Her mother is among the nine people

who work for righteous babe records.

Her parents humored her and bought her a little kids guitar when she

was nine. Michael Meldru was working at the guitar store "He was

kind of a Buffalo Personality, folk singer, barfly, small-time promoter,

poet, degenerate, songwriter guy" says DiFranco. "We just hit it off.

I'm nine, he's 30. I was a precocious kid, and maybe one of the few

people who would listen to him, and he was my friend and mentor"

Meldrum once told Ms. Magazine "I saw a little girl with pigtails down

to her knees, and braces. Big Smile, open eyes, a lot of wonder ... she

had a great voice, a big voice coming out of this very little person ..."

He took her out to a bar on her 11th birthday, she got served.

It's no surprise that DiFranco - like so many people of her generation -

is the product of a broken home. She has been playing the adult for so

long, and redefining the meaning of family in her life, that one can't

help but sense her world-weariness. The difference, though, is that

DiFranco is not cynical. She seems to truly love and depend on her

"family" around her - the crew, the band, the label folks.

One day, riding on the tour bus, DiFranco is reading aloud a glowing

review of Living in Clip to Andy Stochansky, her longtime drummer,

and Jason Mercer, her new bass player (replacing Sara Lee, formerly

of Gang of Four) She mocks the reviews verbosity, while clearly

enjoying the fact that it is overwhelmingly positive. "As the foil for

most of DiFranco's onstage jokes and musings" she reads

"[Stochansky] plays a valuable role by affirming that this singular

performer's art isn't just a girl thing" She looks up at Stochansky and

says "Because you have a cock, it adds a while new dimension.

There's a boy on stage. We can all rest assured."

DiFranco is not an angry person, so comments like these aren't

unnerving. She has an essential brattiness that's the key to her appeal.

When she says "Fuck You" It's with a big toothy smile splashed across

her face.

It doesn't take me long to spot the boyfriends: Andrew Gilchrist (aka

the goat boy, because of his strangely appealing, caprina visage) is also

DiFranco's sound engineer. I see that they both wear the same ring.

One of the first things I notice in the Buffalo house is a framed picture

of Gilchrist, just inside the door.

For years, many people assumed DiFranco was a lesbian. When I ask

her how she defines her sexuality, she says that she doesn't. "I'm

attracted to different things that may or may not have to do with

gender. The person that I'm in love with now - the goat boy - the

thing that makes our relationship so perfect is that it's so dubiously

gendered. We take turns. It's supposed to be 'Oh, big righteous babe

falling in love for a man. Boo hiss taboo betrayal' And it's like 'You

should see him! He's more of a girl than I am" we fell in love, and it

was very tortured because we hurt other people that we were with, and

that's the album Dilate, I'm not playing any of those songs now.

I hate forcing labels on people who avoid them, but or the sake of

conversation, DiFranco seems to be, in practice, a male-oriented

bisexual. When I ask her if she's ever been afraid of men, she blurts

out "They're scary! Yeah!" And then backpedals "But it's the way

we're socialized .... I mean, like, people are just scary fucking

monsters!" She laughs uproariously. "I was really young and in the bar

scene and men were very carnivorous. So men terrified me But now in

my life it's the women what are really carnivorous, and really the most

manipulative. It's bizarre. Like I'm standing onstage playing and I

look down and some woman will wag her tongue at me. Or someone

will scream at me 'Play this! Play that! Talk! Sing!' Imagine if it were

men behaving that way. A few nights ago, some women was yelling

'Sing! Sing!' I looked right at her and said. 'Why don't you just have a

child and boss IT around1"

At the show in Birmingham, Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls turns up on

her motorcycle. She and DiFranco are good friends. "We both have

this part of our brain that makes us think that everybody should and

will be nice and friendly and forthcoming" says DiFranco "And then

we're completely disillusioned. We have all these grand plans. One of

them is the Rolling Thunder Pussy Revue. There's all these women's

festivals going on this summer, and we don't think they're as

adventurous as they could be. Lilth Fair - right away, by the name, you

know they aren't pushing the envelope hard enough. "

After the show, DiFranco and Way hand out in the dressing room, and

at one point, start talking about their tattoo's, specifically one way just

got on her chest. She has an appointment in a few days in New York

with Joan Jett's tattoo artist, a woman, to have it fixed. "The guy talked

me into pitting it on my chest and I was going to put in on my back."

Says ray. "I think he was just trying to talk me into taking my shirt off.

I was, like, ' I've been raped by the tattoo man!" They both laugh.

"I got a tattoo from a guy that wax kind of weird" says DiFranco. "This

thing on the back of my neck is basically a prison tattoo: a couple of

squiggly lines, so simple you could do it with a paring knife. And it

was crocked and asymmetrical. And he was not very friendly"

"Did you feel funny afterwards?" asks Ray

"Yup" says DiFranco, "I felt very angry."

"Did you feel violated?"

"Oh totally," says DiFranco. "I was like, 18, isn't that weird?"

says Ray

"That's when I decided I would only go to women" says DiFranco. "But then

the women who did this, I HATED!"

I can't help but notice that Ani DiFranco seems to be experiencing

some kind of ideological shift where gender I concerned. Part of what

has made feminism appealing once again is that you don't have to hate

men to feel truly empowered. Perhaps she's finding, it's too easy and

reactionary to always say that girls are better.

She calls herself the folksinger. As does everyone else in the stage,

tight crew that compromises the DiFranco family traveling circus. As

in "Where's The Folksinger?" That she calls herself the folksinger is of

note because DiFranco is called so many things, self-made,

independent, feminist, bisexual, folk, punk, singer/songwriter, guitar

player, hero, role model, phenomenon.

When I first encountered DiFranco in Knoxville, I told her I had just

been stopped by a cop for no apparent reason and that he felt it

necessary to search my rental for "drugs or guns or anything illegal"

She related a story form her early touring days, when she was traveling

alone with her guitar through Texas one sweltering summer day -

topless. A cop pulled her over, found her half naked with a box of

cash and cassettes in the trunk, and demanded to know what she was

doing and where she was going. She pleaded with the officer "I'm a

folk singer!!"

Birmingham to Tampa, 600 miles. The band and crew, 11 in all, are

hoped-up tonight as the bus takes off at 1 AM "Bus Surfing!" shouts

DiFranco. Blinking X-mas lights are turned on, and a joint is passed

around. Somebody's making blender drinks with fruit and vodka.

System 7 is pumping form the sound system, and suddenly the bus has

been transformed into a rolling disco. All 11 people crowd into the

front lounge and dance like mad, whooping and hollering and trying to

stand up as the huge bus lumbers around curves and corners. DiFranco,

complaining that she can't dance to this particular choice, changes the

music to James Brown. After an hour of bumping and grinding, people

fall out and sit down, one by one.

DiFranco scooches next to me on a banquette. James Brown is still

playing. We are very stoned. "Dig the lyrics to this song" she says

"Stand up Baby, let me see where you're coming form" Obviously a

cry for social action. And then he says "get involved! Get involved!"

He keeps repeating it. Again a cry for social action" At this point we

are practically sitting on top o one another, her face just inches away.

"He's also an environmentalist, " she says half serious "There's that

song 'what do we need? Solar power!" people think he's saying soul

power. But he's actually saying solar power Again a political message

Wow

There are a couple of things about the folksinger that push the

boundaries of folk music. One is that she is deeply funky. On this tour

she has been opening with a very tribe called quest-ish version of a

poem she wrote called "IQ" [myIQ actually] She pulls off a kind of

1990-East-Coast-hip-hop, diggity-diggity rhyme style with amazing

success for a white girl form Buffalo. She is also a great dancer. In her

ever present KISS boots - silver plated clunkers that add a few inches -

she jerks and swivels her body, with an innate rhythm to rival any

current r&b artist.

The other thing about the folksinger that surprises me is that she is so

funny. Her performances veer into such over-the-top giddiness as to

give one the impression that she is half stand up comic. The rhythm of

her between song spiels is more Roseanne than Joan Baez.

Back on the Bus, after the surfing, I say 'rock and roll is rarely funny"

"yeah right, she says, "All my life I've always felt like the most un-cool

person. Because it's not cool to be happy, it's not cool to be funny.

For me, it's just not cool to be boring. I can't take it. So I'd rather

hang out with the class clowns than the cool guys"

The Tampa Bay performing Arts Center, 6 PM. The DiFranco family

Circus has pulled into town, only to discover that they are surrounded

by surreality. In the Holiday Inn next door, where we are staying, a

Narcotics Anonymous convention is in full swing - everywhere you

look there are ex-drug addicts, everyone of them looking like ten miles

of rough trail. In the complex where DiFranco will perform, a Catholic

high school prom is unfolding.

Outside on the loading dock of the convention center, DiFranco, whose

hair is now bleached blonde, pulls me aside. "I was thinking about

something that you said last night, that you didn't expect my show

would be funny. I've always had this basic understanding of what folk

music is, that is has to do with economics, that it is sub-corporate

music. Folk music is not on the radio, folk music does not make

money, folk music is more community based, politically oriented, of

the people. Rock music is more of a commodity.

"But you made me realize that another major distinction between rock

n roll and folk music is humor. What references in rock n roll do you

have for humor? Rock n Roll takes itself so seriously; folk music never

does. Because it's not cool to be funny, It's corny. My new little

manifesto is that folksingers take everything very seriously except for

themselves. They talk about social issues, political issues, , their

country, their society, their lives, their time, their place. But in this

whole rock n roll milieu, you take nothing seriously, save yourself. It's

so self-serious and tortured and grandiose"

This is, of course, an oversimplification, but she has a point. Suddenly,

Stochansky, who plays DiFranco's straight man on stage, gets dragged

into the conversation.

"He didn't say anything for, like, a year" says DiFranco. "I just kept

turning around and verbally abusing him, and eventually he just started

talking. Except he's always get the audience sympathy. They'd all

turn to Andy and go, "awwwwwwww" fucking perfect job in the

universe. Walk out, hit things with sticks, get sympathy from all the

hot babe-age"

The day before, in Alabama, Stochansky and I had gone for a walk

before the show and found a grassy lawn on which to hang out. He is

what a friend of mine called a "SNAG" a sensitive new age guy. He

and DiFranco have been playing together for six years, and the bond is

deep. "She always felt like family" h said, and then recalled the day

DiFranco met his father, a Ukrainian immigrant. "You are a dirty girl"

he said. To which she replied "And someday, I'm going to be a dirty

old woman"

When Stochansky, who is from Toronto, first started playing with

DiFranco, it was just the two of them onstage, and he was often one of

the only men in the room. He told me about the moment things shifted.

"At X-mas, a couple of years ago, in Vancouver. One night , it just

happened. I came back to the dressing room and said 'Ani, you're not

going to believe this, but there are guys out there. Not only that, but

there are probably more straight people than gay people. ' I went from

playing a primarily female gay audience, to suddenly having all these

guys cheer me on. I immediately felt like "No! I don't want to be in

tune with you!"

Next Page

With Stardom just a compromise away, Ani DiFranco chides her fans, goofs off on the media and wishes major labels would get the bleep off her answering machine. Jonathan Van Meter uncovers the essential brattiness of folks great white hope. Tonight in Knoxville, Ani DiFranco is onstage at the Tennessee Theater doing one of the two things she does best: talking. She is talking to her audience, her fans, and oh, what fanatics they are. Pierced, tattooed, obsessed, sexually ambiguous, passionate, young, noisy, bossy, possessive, and demanding, DiFranco's hair id dyed magenta, her T-shirt is orange, her skintight latex pants are electric lime green. She has never performed here before, and whenever she plays a new town - what her her manager calls "breaking in a new market" - it feels a little bit like she's gone back in time a couple of years, when her audiences were mostly women. New markets always bring out the original, hardcore fans: the dykes. In a few minutes she will start doing the other thing she does best: making music. She will sing a song that she's just recently written. A song that goes, in part, like this: [from little plastic castle] From the shape of your shaved head I recognize your silhouette As you walked out of the sun, and sat down And the sight of your sleepy smile Eclipsed all [the] other people As they paused to sneer at the two girls From out of town The Dykes in the audience will love this song. They will feel validated by it, and why not? It's classic Ani DiFranco. Who else writes songs about sleepy, smiling bald headed girls in a coffee shop, in a small town, getting hostile glances from the locals? The dykes will feel that this song is about them. What's not clear, though, is if they will follow the song to it's slightly irritated conclusion, and realize that it is, quite literally, a song about them People talk About my image Like I come in two dimensions Like lipstick, is a sign of my declining mind Like what I happen to be wearing The day that someone takes a picture Is my statement for all womankind ... But I'm getting ahead of myself. She hasn't sung this song yet. She's still talking. "It's a girl vibe! It's like, a pitch thing!" She does an imitation of the roar of a mixed-gender crowd of a girl crowd. Then she singles out a guy in the front row. "You are a brave man. There is, like one fucking sensitive beautiful, brave man in the audience" Someone shouts out, "Men are pigs!!" and DiFranco brings the proceedings to a grinding halt. "One thing I hate...m" she says, quietly seething. The room falls silent. Her voice rises an octave and into the tone, if not the syntax, of a grade-school teacher admonishing her pupils. "You know, it's really nice to be, like, in the groove of a girl vibe, because there's a feeling of strength, but I so want there to be feeling of inclusion. There's a lot of sad shit that goes down in my songs, that goes down in my world and my life, bit I never think of it as an us vs. them situation. The energy has been sucked up right out of the room. A few songs latter, she talks some more. "I was is New York at a traumatic photo shoot. They kind of go from mildly traumatic to absolutely devastating. It always starts with a dress" She imitates a gay male stylist "Oh, you would look exquisite in this!" I put it on, and it's see through. And I'm like, "Uhmm ... uhm ..." She fiddles with her guitar, pauses for effect. "It was Jugs magazine, so I don't know why I was fighting it" The audience roars with laughter and finally, the bond, the connection, the love, returns. The next day, in a rock club in Birmingham, Alabama, DiFranco is hanging out in her dressing room with candles burning all around her, all the lights soft, waiting for showtime. It occurs to me that in addition to the pressure from the image-making machinery to wear see-through gowns, Ani DiFranco is getting the exact opposite pressure from the other end of the spectrum: the dyke fans and the gender-identity political freaks who feel betrayed is she isn't wearing pants - like lipstick is a sign of her declining mind. When I share this thought she lets loose with frustration and defensiveness. "like I'm supposed to have hammered out this niche for myself now. I'm the stompy-booted, sort of butchy, Go-girl folkstress, and I'm supposed to just roll with that like I'm a caricature of myself.. People try to turn me into my fans, I was thinking that again last night when that chick yelled out, 'men are pigs' I was thinking 'YOU are why they stereotype me' All my life I've been the angry man hating, puppy eating hairy, homely, feminist bitch!"

She runs out of steam, trails off, and looks down, as if slightly embarrassed by the spew of her frustration. "So I guess ... yeah, I cannot be caricature. But a lot of my fans do want it simple, they want it easy. And when I insist on my own stupid personality quirks it can be offensive to them." Outside, fans are gathering, perhaps a couple hundred, waiting to be let in. DiFranco goes to surprisingly great lengths to avoid contact with her fans. She wants to go for a walk before taking the stage tonight, so she does her best to cover up all visible quirks by wearing a plain brown pair of Dickies and a baggy blue sweet shirt. She jerks the hood up over and heads out the stage door. A clean getaway. Not since Bob Dylan plugged in his electric guitar have a group of fans been so freaked by an artists evolution. Since 1990 (when, at the ago of 20, she released her first album, Ani DiFranco, on her own label, Righteous Babe Records), the tiny, 5'3" DiFranco has been at the center of a cult of personality that has slowly grown to epic proportions. She has, quite simply, created a monster. After several homespun, self-produced releases, filled with overly political, often funny, sometimes brilliant, and distinctly old-school feminist songs, DiFranco reached her own apotheosis with the 1995 release Not a Pretty Girl (which sold 112,000 copies). The title track reads like a mission statement for young feminists everywhere. One fan I encountered - a member of a white girl gang from Oregon - told me that "32 flavors," another track, was their team fight song, And then . . . Ani DiFranco met a guy, fell in love, grew her hair out, and became a pretty girl. She even started wearing dresses and lipstick occasionally. Every song on her next album, Dilate, explored the contours of this new relationship: love, love/hate, hate. The album garnered her best reviews to date (it entered the Billboard charts at No. 89 and sold over 174,000 copies), and suddenly DiFranco didn't belong just to the dykes and the feminists and longer. RIGHTEOUS BABE, AN INDIE SUCCESS STORY: Ani DiFranco's label rises up form the grass roots. This was the headline on the cover of Billboard, April 12, 1997. After seven years of being her own boss and touring ceaselessly around the country, after seven years of building a rabidly loyal fan base through playing small bars, coffeehouses, colleges campuses, and folk festivals, after seven years if the best grass roots word of mouth wince Bruce Springstein player the stone pony, Ani DiFranco suddenly popped up on the radar screen of popular culture. But it wasn't so much that her music finally caught fire with a larger audience, or that her potent, confessional lyrics had at once connected to the mainstream. It was that she was making more money per unit that Hootie & the Blowfish. And the story had legs. Both the Wall Street Journal and Time magazine weighed in on the subject. DiFranco found herself in the surreal position of sitting behind a desk on the financial news network being asked to prattle on about profit margins. Forbes magazine even got the Artist Formerly know as Prince - the major label slave himself, and perhaps the only person alive who cranks out more music than DiFranco - on the blower for a comment. "I love Ani DiFranco," he said "She's making four dollars a record and the superstars are only making two dollars, so who's got the better deal?" The music and alternative press have been lavishing praise on DiFranco's music for a few years now, but since her last two releases have cracked the billboard charts - this years double live album Living in Clip debuted at no 59 - the focus has shifted. "Now suddenly, I'm a brilliant strategist" she says "where I used to be this stupid girl with too 'tude for her own good, who's is cutting off her nose to spite her face and the music industry. And everybody would say "You're selling thousands of albums, and we can help you. Don't you want people to hear your music?" And it was like "She does an imitation of Charlie Browns teacher "Wah-Wah-wah-wah" One of those people was Danny Goldberg, president and CEO of Mercury Records. He once bragged to a reporter that Righteous Babe Records never returned his calls. When I talk to him about DiFranco , he is quick to put me in ,y place when I suggest that what she is doing, from a business standpoint, is unique. "I don't think she's reinventing the wheel," he says, a bit defensively, "Fugazi did the same thing, Bad Religion did it for years. It's part of her PR shtick that she has her own label and she makes more per unit on it, and feels more in control of it. I find that less interesting. A lot of people have indie labels. There are very few artists like Ani DiFranco. If she wasn't a good artist and she had her own label, who'd give a shit?"